Ishiuchi Miyako, Photography, & ‘Hiroshima’

- jbourke98

- Jun 12, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 13, 2025

Ishiuchi Miyako, ‘ひろしま/hiroshima’, #71, 2007.

‘The photograph gives off mixed signals.

Stop this [the violence], it urges.

But it also exclaims, What a spectacle!

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (2002), p. 68.

Some images take my breath away. When I came face-to-face with one of Ishiuchi Miyako’s photographs at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art (see the image, above) a couple of weeks ago, I was both shaken and entranced. Photograph #71 is part of Ishiuchi’s ‘ひろしま/hiroshima’ series of 48 colour photographs, first exhibited in 2007, memorializing the aftermath of the A-Bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, resulting in the incineration of 140,000 residents.

The photograph shows a torn, stained dress, originally worn by a Hibakusha (survivor of the A-Bomb) named Hatakemura Takeyo, who had been 1,900 metres from the hypocentre of the atomic bomb when it exploded. The photograph alludes to the unimaginable cruelty of modern warfare: the bodily stains discolouring the dress testifies to a life torn asunder.

But there is a disturbing beauty to the image: the dress appears to float in the air, wafting towards the skies. Although it wasn’t Ishiuchi’s intention, some critics saw in the photograph echoes of Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçon fashion statement of 1981, worryingly dubbed ‘Hiroshima chic’. As Susan Sontag exclaimed, ‘What a spectacle!’

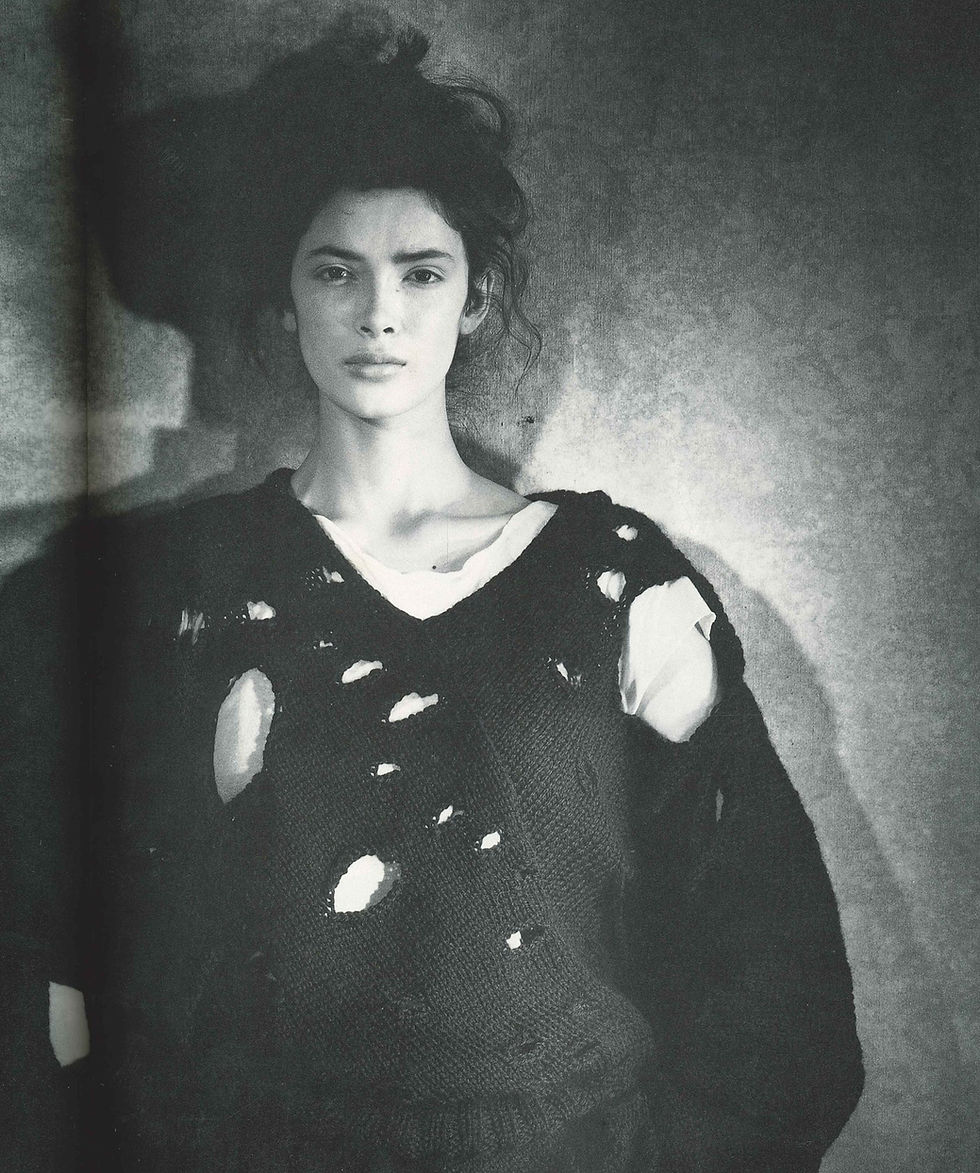

Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçon fashion statement, 1981

For me, however, photograph #71 is haunted by Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, described by Walter Benjamin as the Angel of History. Benjamin writes that the angel’s

face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress. (Benjamin, 1940.)

The dress of this ‘ordinary’ woman in #71 seemed to me to represent such as Angel of History, a witness to the technological ‘progress’ of atomic warfare. The absent women who used to inhabit the dress has turned away from the debris of the destroyed city and her ‘second skin’, the fabric that used to shelter her flesh, soars into the sky. This Angel of History #71 is powerless to either mend the past or determine the future.

Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, 1920

There is something deeply unsettling, though, about turning Hatakemura’s dress into an image of the Angel of History, as I have done. Hatakemura’s dress covered yet ultimately failed to protect a very real 41-year-old Japanese woman going about her daily business on that day in August 1945. The dress is one of thousands of personal items donated to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum by bereaved families and friends as well as surviving victims. In 2007, when Ishiuchi was invited to photograph some of these commemorative items and ihin (objects left by the dead), she was initially hesitant. She was not part of the ‘Bomb generation’ (she was born in 1947) and had never even visited Hiroshima before the commission. In subsequent years, she believed that her ‘outsider’ status had been fortuitous. As she told one interviewer,

Hiroshima represents the history of humanity, so it takes a great deal of emotion to engage it…. I was a stranger. Coming from somewhere else means that there is a sense of distance, and you have to be objectively aware that you’re an outsider. I knew I couldn’t do it otherwise (‘The Story of Two Women’, 2019, p. 199).

She decided to use a hand-held 35mm camera, natural light, and light boxes. The bright white backgrounds are reminiscent of the intense, clear light emitted by the A-Bomb explosion. The ‘floating’ effect was intended to encourage viewers to reflect on the women, men, and children who had worn these clothes. What was important to them? How were they feeling that fateful day? What happened to them? These were questions Ishiuchi also asked. She described removing items of clothing from their archival boxes inside the museum. After ‘gently pressing out the creases of a blouse long folded up”, she would bring the garments ‘into the light of the sun shining through a window’ where, ‘for an instance, the polka dots and floral patterns shimmer and the woman who once wore it rises’.

Ishiuchi was also self-consciously situating her ‘ひろしま/hiroshima’ photographs in opposition to a longer tradition of artistic depictions of Hiroshima after the A-Bomb. Prior to 2007, photographic representations of Hiroshima were dominated by graphic images of suffering, depicted in monochrome. This remains the case today.

In contrast, Ishiuchi wants viewers to notice the vibrancy of the city prior to the atomic attack, with its colourful clothing, fashionable decors, and bustling conviviality. Visual representations of slogans such as ‘Peace!’ and ‘No More Hiroshimas!’ are anathema to her. The ‘ひろしま/hiroshima’ photographs are not even captioned. She insists that, ‘I do not make appeals. I don’t offer captions because I want you to see them with your own eyes and feel with your own words’. Her aim was not to ‘document’ but to ‘resurrect’ the ‘beauty’ of the people who lived in those few minutes before 08.15 on 6 August 1945.

Ishiuchi’s artistic confidence had developed over the three decades prior to her Hiroshima series. She had originally studied textile design and weaving at Tama Art University (Tokyo), turning to photography only at the age of 28. Her earliest photographic project focussed on her hometown of Yokosuka, a U.S. naval base that had been established in the immediate aftermath of the American destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The grainy photographs of Yokosuka Story (1977) evoke a sense of resentment and suppressed as well as unsuppressed violence (the Americans stationed at the base raped local girls and women). The series was followed by Apartment (1978) and Endless Night (1981) with their obsessive gaze on spaces of abandonment and rejection. They also gesture towards Ishiuchu’s lifelong fascinating with scars and skin textures. In 1989, she exhibited a series entitled 1·9·4·7 focussing on the hands and feet of women born in 1947, the same year as her birth. Perhaps as an attempt to reconcile herself with her mother, with whom she had a troubled relationship (this was despite taking her mother’s maiden name as her artistic-working name; her birthname was Fujikura Yōko), between 2000 and 2005, Ishiuchi produced photographs entitled Mother’s. These were a series of tender and often unsettling depictions of her mother, before and after her death, including intimate photographs of her mother’s lace underwear, dentures, cosmetics, worn gloves, hairbrushes, and other belongings. More recently, Mother’s led to a commission entitled Frida in 2015, based on the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s wardrobe and personal belongings. Like ‘ひろしま/hiroshima’, it shows a concern with the traces people leave behind after death, beauty despite acts of destruction, and the role of art in making memory as well as history.

This is what makes the ‘ひろしま/hiroshima’ photographs so powerful. While some critics accuse Ishiuchi of contributing to the silencing of the Hibakusha, or even of universalising the experience of violence by detaching it from personal life stories, when I stood in front of photograph #71 its ethereal beauty seemed to be a reflective and respectful dialogue with the dead. Ishiuchi doesn’t pretend that this dialogue is anything more than a momentary spark of recognition; simply representational fragments gesturing back to past wholeness, to lives lived differently. As she admits, she ‘can’t photograph the past. I can only photograph what happens in the moment I encounter this particular object, my most personal reactions, what I feel and see’. While the dresses themselves – donated and then stored in the vaults of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum – are intended as spectacular metonyms of destruction, Ishiuchi’s photographs of them encourage us to perform the memory-work that both remembers the specific harms inflicted on the original owners and makes that mental leap to current atrocities in Gaza or the Ukraine.

References:

Benjamin, Walter, ‘On the Concept of History’, 1940 at

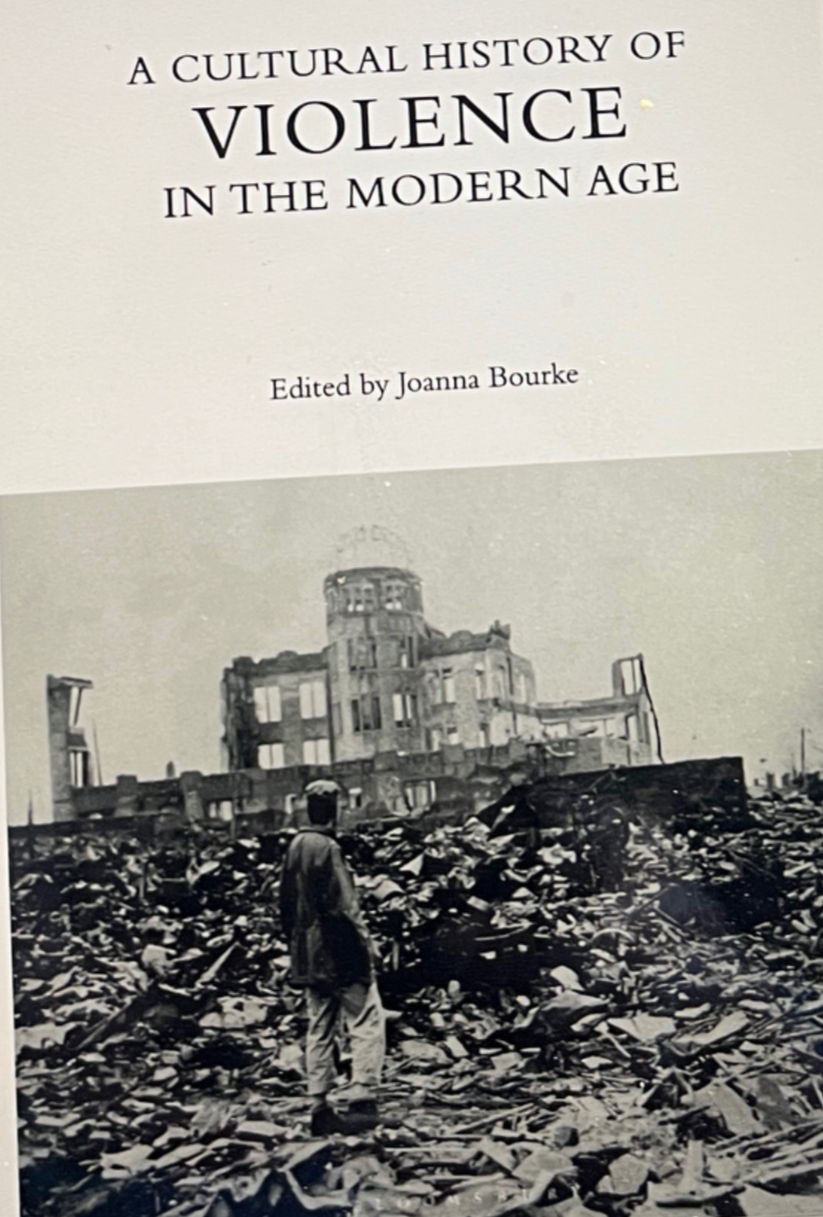

Bourke, Joanna, ‘Introduction’, in Bourke (ed.), War and Art. A Visual History of Modern Conflict (Reaktion Books, 2017), pp. 7-41

Igarashi, Yoshikuni, ‘Are We Allowed to Find Beauty in the Face of Death and Destruction? Ishiuchi Miyako’s Hiroshima and Postwar Japan’, Japan Review, 39 (2024), pp. 99-130

Sontag, Susan, Regarding the Pain of Others (Picador, 2002)

‘The Story of Two Women’, by Ishiuchi Miyako, Iwasaki Chihiro, Ueno Chizuko, and Tajima Miho, Review of Japanese Culture and Society, 31 (2019), pp. 189-202

Ishiuchi Miyako has won many honours. For example, she represented the Japan Pavilion at the Vienna Biennale in 2005 and, in 2014, won the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography, the most prestigious photography prize in the world.

Comments